The Cycle of Compromise, Vulgarization, and Disillusion: From 1955 to 1984 to 2010.THE CONSERVATIVE MEDIA CULTURE:POLITICIANS AS MOUTHPIECES,

TALKING HEADS AS DEMAGOGUES

"Intellectual conservatism" remains unfathomable till you make a distinction between a realm of political

thought and a realm of political

practice, a distinction that seems now to belong to another era.

But first consider the world we live in now. For those who have experienced only the conservative media culture of 2010, any world in which this distinction matters may be unimaginable. Today one can distinguish only between a realm of professional talking heads and a realm of politicians and their staffers and professional party spokesmen, one group getting its living from media revenues, the other getting its living from government salaries or party coffers. To one group you are an audience member, a commercial advertising target and a potential book-buyer; to the other group you are a voter and potential donor. As I write this in 2010, the politicians are hostages of the talking heads. (But the situation could easily change if the talking heads started seeking political office.) In this scheme there is no source of serious original thought about politics.

If the source exists, it is invisible.

If conservatism is a deliberate choice for the old and the unoriginal, how could there be "original" conservative thought? Well, if conservatism's fundamental treasury of wisdom is western philosophy itself, then there is always something more to be mined from the past and applied to the present, something forgotten, underappreciated, misunderstood. This is especially true for a nation whose founders, however wise, were still men of their age, Enlightenment Protestants. Conservatism respects their "filtered" version of the Western tradition embodied in our constitutional system but also looks behind the filter.

Conservatives do believe in innovation insofar as they believe in the free market as the generator and tester of invention. But philosophy is not of the market. It is an alternative to the market. The freedom it needs in order to flourish is freedom from pricetags. It needs the support of people who believe that there is something more important than money, and are willing to waste money on it. In his purest form, the political philosopher will spit on an invitation to belong to any political party, for the truth does not belong to a party. It will take a self-sacrificing devotion to the ideal of truth if you are to suffer willingly the philosopher's contempt for your petty political agenda. In a word, don't expect to be thanked.

As for the "talking heads" of our day—the pundits, commentators, and hosts of TV and radio—these are debased imitations of the older "conservative intellectual." Among them are the remaining columnists of print journalism. At their best, they are effective critics of the politicians of their own side.

At their worst, however, they are no better than script-writers for the politicians. They are the contrivers of the proverbial daily "talking points," the material that will appeal to your anxieties and foment your morbid curiosity and hysteria. They scan continuously for false controversies that will keep you addicted to the daily news cycle. Each "talking head" wants you to identify with him as your political savior and ersatz friend, to encourage your dependency. And of course you trust in him if he is the one who made you care about politics at all, and perhaps got you to read the Constitution for the first time, or

The Road to Serfdom. Usually, of course, the "talking head" only wants you to buy and read his own book, which isn't much more than a transcription of his daily on-the-air monologue.

The false controversies arise when political opponents stumble. I call them "false," but what they really are is symbolic, engaging the passions more than the reason, but not completely unreasonable when they are decoded. The result of this continuous "training" in political feelings and petty causes is not completely evil if the respective audiences of the new media culture (two audiences, obviously, a rightist one and a leftist one) really learn something about government and issues. One may ask whether this media culture does more harm than good, whether there is more deception and manipulation than learning, or whether it would be better to let sleeping dogs lie. An optimist will say that the more talk there is, the more people will learn to discriminate; over time they will learn to discern truth from lies. This much all must admit: once the game has started, there is no stopping it; you must play it out; you can only hope that each side plays its hand fully. Or, to change the metaphor from poker to team sports, one hopes that the blows of many kicking feet in the fullness of play will ultimately level the playing field, even if the resulting level is low.

The present situation came about through the deterioration of an older one. In the age before continuous cable "news" and talk radio, there were clearly visible sources of original political thought called "conservative intellectuals." And what is an "intellectual"? Something more than a talking head, and something other than a politician. Of course there is much more to say who and what they are, and where their authority comes from. At first let's allow the question to answer itself somewhat by making the distinction between political

thought and political

practice.The conservative intellectuals were the game-changers of their time. Before them, there was no theoretical component in the world of conservative politics and policies whatsoever. No "ideas," only unwilling captivity to the agendas of liberals, and an attitude of resistance; at best only an occasional attempt to recover the meaning of a phrase out of the

Federalist Papers.Today, some concepts from the first generation of conservative intellectuals are still floating around as debased verbiage in the fog of the media culture. The politicians and the talking heads inhale and exhale this fog back and forth between each other. There is no new content between them, and their roles are confused. As imitation conservative intellectuals, the "talking heads" are themselves political operatives though outside the realm of government. Meanwhile the conservative politicians—who have learned to talk in a way they never did before Reagan—are now, as inept Reagans, a kind of inept "talking heads" from within government. On one side you have demagogues elected by the media market; on the other side you have political "professors" whose academic chair is their seat in congress.

So let us make the distinction, as it arose in the

1950's and might still be seen clearly in the

1980's, between a realm of political

thought and a realm of political

practice, or between a realm of reflection on political and economic systems, on culture and on history, and a realm of propagandizing, electioneering, and legislative agendas. In other words, between a realm in which a man is more likely to be honest with himself and a realm in which he will be tempted to deceive others in order to obtain power. The realm of thought was the realm of magazines and universities; the realm of practice was the realm of government.

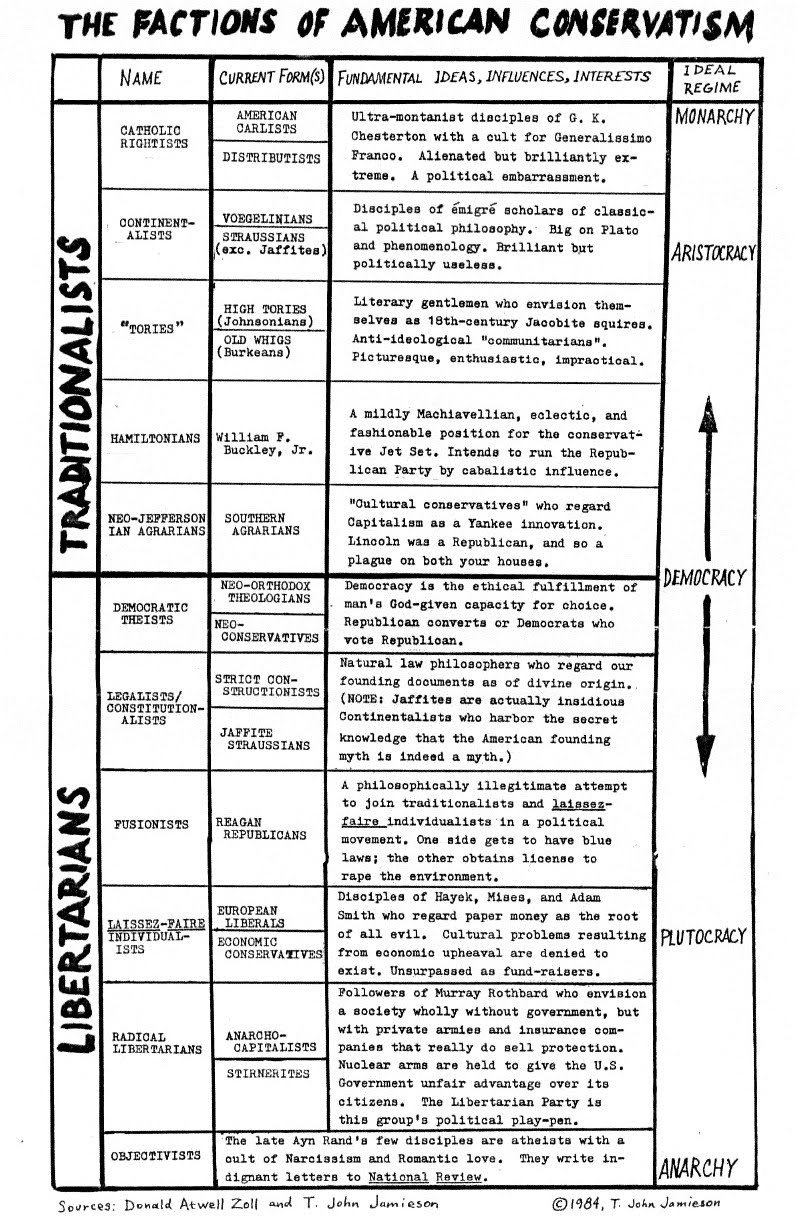

(Click on this chart which summarizes the distinction.)

(Click on this chart which summarizes the distinction.)

(There was also a distinction to make in the 1980's between the realm of pure scholarship and the realm of foundations supposedly dedicated to the support of such scholarship, a distinction between what scholars did in their search for truth and what a foundation's organizers and fundraisers did to cultivate an image that would attract donors.)

INTELLECTUALS VS POLITICIANS

In 2010, then, all media discourse on politics appears to be a propaganda program in the service of political parties and candidates and also a business which enriches certain media operators. In 1955, the movement of "intellectual conservatives," founded by Bill Buckley and centered around his magazine, had no meaningful access to political power. It was a movement of speculation, criticism, and self-definition:- speculation on the threats to Western civilization as well as the American bourgeois social order,

- criticism of the political practice of both Democrats and Republicans,

- self-definition by the self-begotten American conservatives of their identity.

This movement was an élite, a vanguard, seeking the means to persuade other élites and also to create a middlebrow mass constituency. (A hypocritical polemic against élites by élites is one of the features of 2010's propagandistic climate.) The most important convert of Buckley's movement in the practical realm, its supreme agent for reaching the mass, was Ronald Reagan, who read every issue of National Review, beginning with the first.

Americans do not understand that society lives through its élites. An élite without relation to a mass (an audience, a constituency) is only a sect or a hobby unless it is a vanguard preparing to reach and lead a mass. The truth about élites is an unutterable secret. Whoever speaks it risks being called a "fascist." The demagogues and propagandists have done their work well.

At the midpoint between 1955 and 2010, in the early years of Reagan's presidency, the "intellectual conservatives" had access to power. But the realms of thought and power were still institutionally distinct. On the one hand there were the professors of literature, history, and political science and economy, and also the authors of ghost stories and elegant essays, all still engaged in that mental project of speculation, criticism, and self-definition as the producers of a literary product called "conservative thought." On the other hand there were the politicians and grey eminences in the corridors of power, pollsters and vote-counters, policy wonks and party hacks, who could be called the consumers of the literary product—and, by nature if not always by intention, its corrupters. Hence the situation arose in 1983-84 when the producers realized that their hope of change was not being fulfilled, and their disillusioned cry went up that "we hold office but we do not hold power," signaling an incomplete awakening to the nature of power, to the necessity of compromise and gradualism, and to the ongoing general resistance of the realm of practice to the realm of thought.

Don't we all know that politics are corrupt and that publicity deforms in order to explain and persuade?

When reading old books on the period, one needs to remember that liberal journalists took no interest in keeping the distinction between these realms clear while portraying what they believed (and still believe) to be the great conservative conspiracy. So, in their general description of conservatism, the shallowness and the non-sequiturs of Republican political propaganda became a stick with which to beat the conservative intellectuals; meanwhile the free exploration of political theory by the conservative intellectuals served as evidence of the "extremeness" and dangerousness of Republican politics.

True believers in communism might still be found who defend their belief by claiming that the system has never really been tried: all so-called communist regimes have deviated so far from the original definition or plan that they cannot honestly be cited as evidence of the system's un-workableness. I am not making any such case for American intellectual conservatism, or any case for it at all. I'm only saying that one must go to the speculative creators of conservative doctrine—instead of its often questionable interpreters and "marketers"—just to know what it is. And I'm saying also that a flourishing conservative movement must again allow a privileged space for these creators to do what they do, unmolested, above and apart from the political tar pit. Otherwise, one might say, the professional corrupters of doctrine will have nothing new to corrupt.

Reagan was "the great communicator" because he was a practical politician who understood what the intellectual conservatives said, what portion of it to use to get votes, and how to use it. How his intentions for institutional change were compromised in their implementation is a complex subject involving many factors, including a non-intellectual wife who warned him, "Don't be one of the true believers, Ronnie, wrapping yourself in the flag and jumping off a cliff." Putting aside Caesar's wife, suffice it to say for now that the grey eminences, by nature cynical, were characteristically cynical about transforming the literary product into slogans and propaganda as well as policy, and about preserving the appearance that they were implementing the president's intentions authentically. It's an age-old story, but this was the first modern president from the right who was concerned about principle—and, so far, the only one.

Any conservative principle can be corrupted in its implementation. One might allow for a certain amount of slippage between the plan and the execution, but sometimes it becomes catastrophic. Obvious example: Deregulation of the banking industry was justified, in general, by the principle of the free market. But the free market principle, which says that innovation and creative risk will benefit almost everyone if there is success, also allows for the possibility for failure... in which case the risk-takers will suffer the consequences of their imprudence or simple bad luck. We all know now that only half the program was implemented; there was no risk for the bankers; the controls over risk-taking were removed without a commitment to let the bankers, their investors, and depositors suffer the consequences of failure. That was the fault of conservative politicians who lied when they said they were implementing a free market solution. Liberal politicians are responsible for compounding the disaster with their insistence on loans to unworthy receivers of loans. When conservatives compromised with liberals to have the deregulation they wanted, or when they pretended that these "sub-prime" loans were part of laissez-faire, they became culpable. This is an economic example, however, the least interesting part of conservatism to me.

The only living "idea" politician to compare with Reagan is Newton Leroy Gingrich, but the comparison comes out unfavorably for the latter. Speaker Gingrich uses concepts like kleenex. The quickest index of his fakery might be his enthusiasm for "Futurist" Alvin Toffler, which he shares with Vice President Albert Gore. Gingrich proves why political operatives cannot be used to define intellectual conservatism.

The struggle of political life is that of making compromises without being compromised: Republican and Democrat legislators must compromise with each other, and the maker of any plan must compromise with "unforeseen realities" as he meets them "on the ground." But many Reagan administration operatives, often mere Republican operatives, recognized power as the only reality. Practical men often hold the life of the mind in contempt, of course, and they regard the talk of intellectuals as only talk, no more substantial than the talk of politicians, probably less so. The talk has value to them only if it collects votes or dollars.

The political operative (liberal or conservative) gives himself away at last when he says to you, like an uncle who has your best interest at heart, "We can't be caught believing our own propaganda."

That may come as a shock to some innocent young readers. I say it only to clarify how my real topic is, and must be, intellectual conservatism and not the slogans of conservative politicians. We must return to that élite realm of theorizing if we are to have an élite vanguard again. But the story of intellectual conservatism is also a story worth telling for its own sake as a story of character. The conservative intellectuals themselves were almost more interesting than their doctrines.

Click on the chart below for a summary of the attitudes of intellectuals and politicians towards each other as experienced in the 1980's. The dynamics of the attitudes clarify the fundamental difference between the realm of thought and the realm of practice.

INTELLECTUALS vs MIDDLEMEN

There was a middle realm between the respective realms of the intellectuals and the politicians, that of the organizers and fundraisers of think-tanks and other curious hybrid organizations. The think-tanks (such as Dr. Edwin Feulner's Heritage Foundation) were supposed to subsidize the growth of more literary product (the pure research of conservatism) and also the development of position papers and plans (the applied research) that would turn into policies and legislation. Under Reagan, this meant that a conservative think-tank was his administration's off-site private arm, its policy brain, also its doctrinal monitor and prodding conscience. As time went on, the think tanks more and more resembled political lobbies, under the cover of giving "lifetime achievement" awards and testimonial dinners for established intellectual conservative writers. The lobbying especially compromised the intellectual mission when it was tailored to the legislative agendas of corporate interests who funded the think-tanks.

The "other curious hybrid organizations" included tax-exempt foundations that evangelized the public for particular right-wing causes and published little magazines, sometimes providing scholarships or research grants or furnishing conservative books to college students. In this group I would even include Hillsdale College during the presidency of George C. Roche, who found access to virtually limitless private funding when he declared that his school would no longer take federal funding. His public evangelizing in the school's name included the newsletter Imprimis, political issue conferences at a ski resort, and even a television program, "Counterpoint" undertaken with the help of Ted Turner. Roche had learned his trade as an operative with another hybrid, the Foundation for Economic Education.

These men of the middle realm would be addressed as "Dr." though they did not seem to be practicing scholars. The original generation of conservative intellectuals would write, speak, and teach under their aegis but complain privately that appearance was not reality. While the conservative intellectuals believed that Reagan administration functionaries had, for the sake of maintaining power, compromised their message or given it less regard than it deserved, the sponsorship which these middle-realm institutions provided for unapplied conservative research was in danger of being lost if one could not show immediate and tangible results. If a certain kind of scholarship couldn't "pay its own way," a fundraiser might say it failed to justify itself by free market principles. A journal of political ideas would always be under pressure to turn into a journal of political issues, and to abandon its scholarly audience for a popular one. And perhaps to have more pictures and slick graphics and fewer footnotes.

Whether through the lust for endless expansion or through the need for bare surivival, a middle-realm institution was always in danger of forgetting its raison d'être and letting the mission fade into an endless cycle of fundraising for its own sake. That would mean exploiting the renown of conservative scholars whose names appeared on its letterhead.

Could it be another way? I don't condemn these organizations outright. Intellectuals too can be naïve and over-trusting; they can also succumb to power worship and the worship of money. They can also be rather touchy and fastidious, and frustrating for the practical men to deal with. And all organizations tend towards a preoccupation with their own perpetuation. As for the pressure to manifest results, the need to be selective in one's projects really did arise from a funding drop. After Reagan won, I often heard the story often that donors were saying, "We won, why do we still need intellectuals and scholars?" Surely the money was still out there, but was being diverted from pure study to re-election campaigns and lobbying.

Bear in mind that the scarcity of funds for intellectual projects was a particular problem for conservatives, a problem liberals generally did not have. Because liberals "owned" the universities and the political establishment and therefore the interlocking directorates of all great charitable endeavors, they controlled the great foundations that funded scholarly work—and sent the money to leftist causes that would make the great capitalists who earned the money turn over in their graves. The conservatives did have their generous donors, and also their manipulative donors, but somehow year after year the conservative projects barely squeaked by.

Put the politicians and operators, the think-tank promoters, and the "pure" intellectuals together and you have the sociological field of conservative politics at this peak moment. If you understand this field, then you understand who the members of The Philadelphia Society were, the group whose meeting I covered for Harper's in 1984. And you begin to understand the friction between the practical men and the theoretical men, over and above the friction between the intellectual conservative factions themselves. It is the theoretical men and their factions who form the topic of this essay, and you must not be distracted by the others.

Nonetheless, to understand my story, you must feel some of the disgust of the original intellectuals in 1984 when they saw how they were failing, beyond a certain point, to "sell" their own message, and when the middlemen were overselling it for them. I heard the title of a famous conservative book repeated over and over: Ideas Have Consequences. If only the estate of the deceased author, Richard Weaver, had been able to collect a royalty every time the title was applied, or misapplied, as a slogan to sell a conference or justify the existence of a think-tank, the Richard Weaver Estate would have been big enough to finance its own staff of cynical professionals. The point came when I had seen too much of the cynical professionals, and I wanted to rewrite the slogan as Insequential Ideas Have Conned.

TO SUMMARIZE THE PROBLEM

As I explain the chart in 2010, I cannot take anything for granted about what an audience might know, or might believe they know, regarding the chart's subject. The media culture immerses us today in talk about political identities and symbolic issues, a discourse in which all terms are constantly emptied of presumed meanings and stuffed with new, convenient meanings, for the short-term gain of some rhetorical point. This recirculating verbal flux erases history, as well as meaning, whenever a pundit tries to anchor his semblance of a theory with misbegotten references to dead presidents, "founding fathers," court decrees, wars and financial panics. It is all for publicity and propaganda.

In this climate of amnesia and aphasia, the individual who gets attention when he calls himself an "intellectual conservative" turns out to be a prissy professor trying to shield himself from blame for the policies of anti-intellectual "conservative" politicians, or a pundit who is the lapdog of liberal media, happy to let liberals decree what is permissible for a conservative to think. The phrase is reduced to one platitude among other meaningless compounds such as "public intellectual," "intellectual integrity," "informed debate," and "civil society"—the latter having lost its value as the Hegelian bürgerliche Gesellschaft, sentimentalized now into a Japanese tea ceremony.

The new world is a vulgarer world, and yet disdain of it can be self-serving. It is also a world free of responsibility. In 2010 you might come to believe that the few sectarian progeny of the original conservative intellectuals—both orthodox and deviant—are happy that Buckley is dead. And Reagan too, for that matter. Many soi-disant Traditionalists seem happy, in some of their crankier little journals and obscure institutes, to have no possible relationship to political power or practice and likewise no relationship to an overarching conservative establishment that might check their extravagances. Extravagances, I must add, that exaggerate the worst tendencies of their respective progenitors in the original conservative movement, now dead and unable to chastise or disown them. The nativists are glad to preach sociobiology without fear of ostracism. The neo-pagans are glad that they no longer need pay lip service to the "Judeo-Christian tradition." The isolationists gloat over the failure of neoconservative geopolitics. Meanwhile in another camp, the Libertarian economists are happy not to be disturbed in their exclusive concern with free markets and the minimalist state; the Libertarian libertines are comfortably untroubled by issues of virtue and Irving Babbitt's "inner check"; and the pious Libertarian Calvinists may go on venerating the Mayflower Compact without giving a thought to the Pope, even as the Anti-Christ of Reformation diatribe. In yet another camp, the hated Neoconservatives enjoy their emancipation from the sentimentalization of village and agrarian life in the nineteenth century, while planning how to exploit the Murdoch media to elect the next scion of the Bush family. This is a mess.

I am calling attention to the first-generation intellectual conservatives of Buckley's National Review as an antidote to this climate of oblivion and irresponsibility. All the essential issues for the definition of an American rightist position were raised between 1955 and 1985. The possibility of writing a "conservative ideology" was discussed—and the exercise of debating the possibility whether such a thing could exist was as instructive as any debate over its possible content. The point of breakdown between the "traditionalist" and "libertarian" tendencies was fully explored, and the exploration exposed the contradictions in American political culture itself. This is the point to which we must return in order to recast or reconceive the American right, both in form and in content, as a movement with a coherent position and with a clear voice above the media noise.

Let us go back in time...