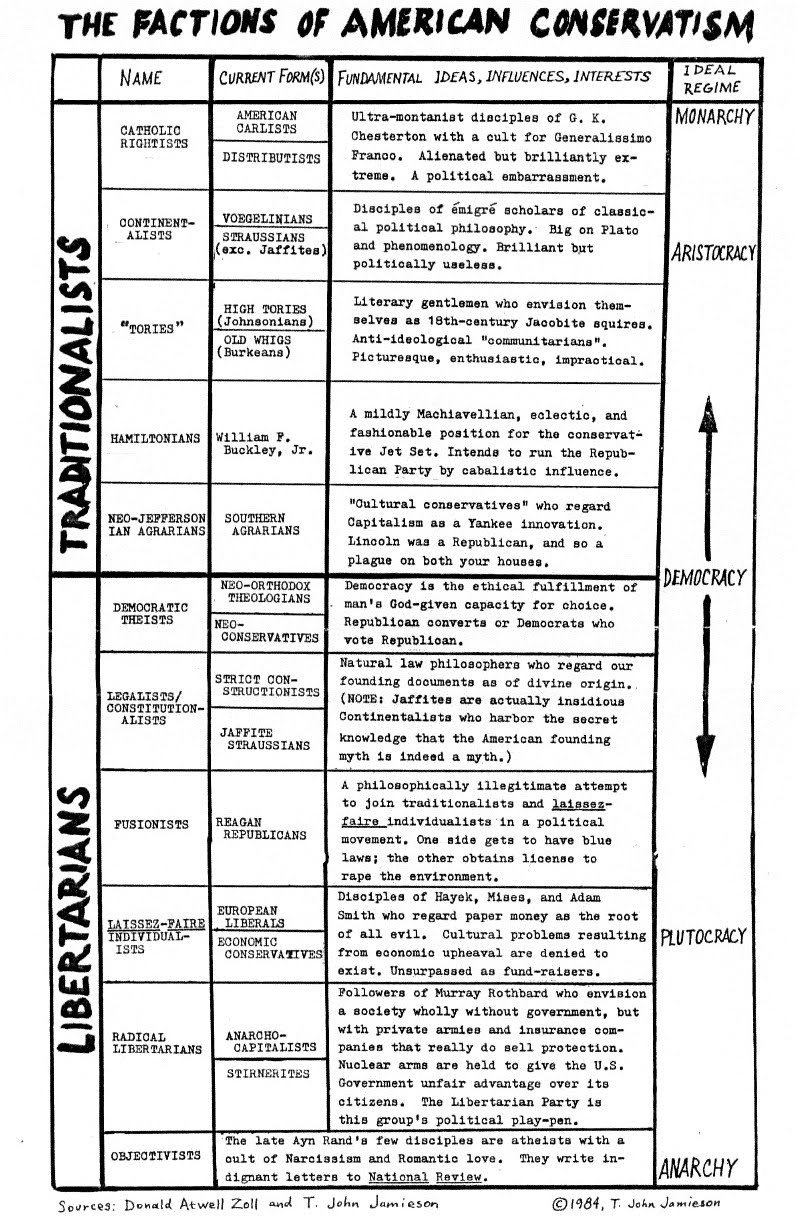

The essay below explains the chart. First I distinguish the realm of the "pure" intellectual from the realm of the political practitioner: the former is a realm in which men are more likely to be true to themselves as they seek to understand the causes of things; the latter is a realm in which men are more likely to try to deceive other men. The first is more relevant to the chart—and easier to map.

Next I define "intellectual conservative" in the abstract. Then I recount the now-forgotten history of the movement's origins in William F. Buckley, Jr.'s magazine National Review. Conservatism is about nothing if not history, and conservatism has its own history.

The story matters because it shows how conservatives at first had it almost right, then went wrong, lost perspective, and wasted their opportunities. That's the point to which a new intellectual conservative vanguard must return to pick up the thread—if such a vanguard is ever born. As I explain here, the circumstances that produced a Buckley may never occur again.

The factions of the chart still matter to intellectual conservatives, for whom self-definition is a never-ending personal project and whose identity depends on shades of difference. Their factional tendency indicates not just a Freudian narcissism of small differences but often a seriousness about ultimate issues above... beneath... and beyond... politics. At least among those who are serious. Even when there is no intellectual conservative movement to which one can belong, the act of claiming an identity remains a matter of personal integrity: one "possesses one's soul in silence," as a late Victorian might say in a quietist mood.

This story is also the story of an article I wrote for Harper's Magazine in 1984 that could not be published. The situation I described in the article blew up two years later and became the subject of an annoying article in The New Republic by John Judis. I was ahead of my time.

If I were less serious about my subject, I would turn the chart into an automated online "test" so that any reader could answer ten questions to find out just what species of conservative he or she is, perhaps to seek a compatible marriage partner. I'll leave that to others. There is plenty of caricature built into the story already, mainly because of the "great men" who were determined to make themselves into caricatures. Some were born with a healthy sense of absurdity; some made themselves absurd; others had absurdity thrust upon them. The alternative to all that is the absurdity of liberalism.

No comments:

Post a Comment